The Families Who Helped Build A Legacy: The 1830s & 1860s

In Fort Bend County, on land that later became known as the George Ranch, the Jones and Ryon families were slave owners. Henry Jones, the Ranch’s founder, had acquired 47 slaves through purchase, trade and birth by his death in 1861. Likewise, Polly Ryon and her husband William owned 16 slaves by the end of the Civil War. While nothing can ever justify the practice of slavery, the story of the George family legacy cannot properly be told without acknowledging and examining the contributions of the enslaved individuals and families who helped build the Ranch.

1830s: The Edwards & Martin Families

The Edwards Family

Arcy Morton — Born into slavery in North Carolina in the 1790s, Arcy is thought to have accompanied Henry Jones and his family on the difficult trek to Texas in 1822. As a domestic slave, Arcy helped the Joneses build a home in this new frontier, cooking for the family and helping tend to the children. She also raised a family of her own, including son Jack (b.1817) and daughters Celia (b.1830), Jane (b.1833) and Caroline (b.1835). She became the matriarch of the sprawling Edwards family.

Firema Edwards — Born in Africa in 1826, Firema (also referred to as Firmna) was brought to Cuba along with 80 other slaves on August 29, 1836. They were then illegally smuggled into Texas by slave trader Monroe Edwards and his partner Christopher Dart. After a dispute broke out between the partners, the slaves were confiscated by the Brazoria County Sheriff and were acquired by the Jones family between 1836 and 1850. He later married Arcy’s daughter Celia and the couple had three children: Mary (b.1844), Cain (b.1848) and Alfred (b.186?). His location in slave census records indicates that he probably farmed for the family at the time, a skill he would use for his own advantage in the future.

The Martin Family

Peter Martin — Peter Martin was born into slavery in Georgia between 1800 and 1810. In 1824, he accompanied his owner Wyly Martin with 100 head of cattle to settle Wyly’s new land grant in Stephen F. Austin’s colony. Sometime between 1819 and 1829, Martin was permitted to marry Judith, who worked as a slave for several Jones family members.

Peter played an active role in the Texas Revolution, carrying supplies to the Texian Army from San Felipe to San Antonio. He also proved to be an adept ranch manager, taking charge of the stock farm from an often-absentee Martin.

By 1835, Wyly began taking steps to emancipate Peter in his will. At the time, freed slaves were not allowed to remain in Texas. In 1839, Wyly petitioned the newly-formed Texas Congress to allow Peter to stay in Texas after his emancipation. After a heated debate, Congress approved the bill and Peter became the first emancipated slave legally permitted to remain in Texas. Wyly died in 1842 and Peter gained his freedom.

Peter continued ranching after Wyly’s death — and when Texas entered the United States at the end of 1845, Peter was ranked 23rd out of 146 ranchers for the size of his herd in Fort Bend County.

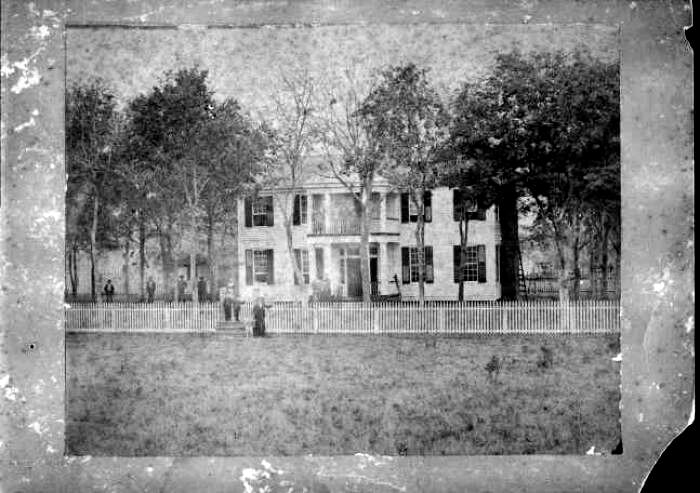

This circa-1870s image is thought to be the only surviving image of the Ryon Prairie Home. Several African American individuals are pictured in the front yard.

1860s: The Edwards, Martin & Jones Families

The Edwards Family

Firema & Celia Edwards — In 1865, Firema and Celia found themselves free at the ages 39 and 35. For unknown reasons, they chose the last name Edwards, the same name as the illegal slave trader who brought Firema to Texas.

In 1866, Firema, Celia and their children Cain and Mary signed a labor contract with William Ryon. Ryon agreed to provide “good” quarters, firewood, food and medical care. In return, they would be expected to work no more than 10 hours per day and would receive in-kind payments of one-fourth of the cotton and corn crop to be paid at the end of the year. In addition, the freedmen would pay one-fourth of the expenses of ginning and marketing the crop.

Firema, along with many other former slaves of the area, voted at the earliest opportunity sometime between 1867 and 1869.

In 1884, Firema and Celia fulfilled the dream of many former slaves by becoming landowners. This land and the accompanying home built by their son Cain remained in descendants’ hands into the modern era.

The Martin Family

Judith Martin — After his emancipation, Peter settled down as a rancher, buying a homestead of his own. With the profits from his operation, he effectively “rented” his wife and children from their owner so they could reside with him at his ranch.

In 1863, Peter died; Judith and her children were evicted from their home and the property was sold. She protested, but at the time had no legal rights to inherit property or sue in court. Though she did receive the profits from the sale, she vowed to continue to work to claim her former land “while she had breath in her body.”

Peter & Judith Martin’s house as it stood in Richmond in 2012. It has since been demolished.

After her own emancipation in 1865, she determinedly set out to regain what had been forcibly taken away from her. With the support and backing of William and Polly Ryon, she petitioned the 21st District Court in Fort Bend County in October 1871 for the return of her husband’s property and her legal right to own it. After a brief trial in July 1872, the jury ruled in her favor; when it was later appealed, the Supreme Court of Texas affirmed the lower court’s decision.

The Jones Family

Cora Fenton Jones — Collie, who later took the name Cora, was purchased by William Ryon in 1852 at the age of 25. She served as cook for the family for many years. In 1860, she married Henry’s slave Bob. Cora had several children before her marriage to Bob, including Sam Ryon. With Bob, she had three children: Louisa, Y. Union and Millburn. The couple had a strong relationship with Polly Ryon throughout their lives and their children would go on to leave a lasting legacy on the Ranch and in Fort Bend County.

This information originated as a pop-up Juneteenth exhibit at the George Ranch Historical Park. Most of the research came from Michael R. Moore’s thesis titled, “Settlers, Slaves, Sharecroppers, and Stockhands: A Texas Plantation-Ranch, 1824-1896.” Moore is a former executive director of the Fort Bend History Association; his thesis can be found at the Houston Public Library.